|

|

|

JULY 2005

by Alex Miller-Mignone

All historic periods speak strongly to the people who inhabit them; some also speak to the generations which follow, and of these, one would be hard pressed to name a period more magnetic and captivating than Tudor England. Dominated by the head-chopping, wife-swapping, majestic figure of Henry VIII, it is peopled with such memorable characters as Anne Boleyn, Sir Thomas More and Cardinal Wolsey, Bloody Mary, Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh, the Earl of Essex and, of course, the Virgin Queen herself, Elizabeth Tudor, and her hapless cousin Mary, Queen of Scots.

These two remarkable women, sovereign queens in an age which still considered the rule of women to be an unnatural, monstrous perversion of divine law, are perhaps the best-known females of their time. Biographies of both still appear almost annually, and the fascination which captivated their contemporaries continues to hold us in thrall some five centuries later.

Although closely related, and near neighbors on their island, the two never met, but their lives were inextricably intertwined, their destinies irrevocably linked, and their aims and goals constantly at cross-purposes. Their strange, see-saw relationship, wherein it seemed that what was good for one was inevitably bad for the other, stretched across nearly three decades of European history, until its bloody culmination in the judicial execution of the one by the other, an act which, in its own way, served as an apotheosis for both.

For, as one of Mary’s more popular mottoes stated, “In my end is my beginning,” and with her death the ill-fated Queen of Scots achieved a status of martyrdom for her faith and a respect and enduring glamour which the events of her turbulent and scandalous past would have precluded had she died at peace in her bed. And for Elizabeth, the removal of the “bosom serpent” whose life she had protected for almost 20 years, to the intolerable risk of her own, elevated her to the realm of the semi-divine, a cultural and emotional icon of the Virgin Queen to replace the Virgin Mother whose worship her father had rejected in his break from the Church of Rome.

Both the contrasts and the similarities between these two remarkable women are astounding, and the conflict between them so pervasive, as to suggest a more than ordinary political basis for the relationship. If we take a look at history through the astrological lens, and specifically via the nativities of these two queens, we get a picture of just how true it is, that character determines destiny.

Born nine years apart, the cousins were both descendants of Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch, who led England out of the internecine struggle of the Wars of the Roses and set the country on a firm economic foundation. Elizabeth Tudor was his granddaughter, the child of his son Henry VIII by his second wife Anne Boleyn, for whom he defied the Catholic Church, established a new religion and risked his soul. Mary Stuart was Henry VII’s great-granddaughter, descendant of his daughter Margaret who had married James IV of Scotland.

But this close familial relationship did not preclude conflict—Henry VIII frequently invaded Scotland, and his armies were in fact responsible for his brother-in-law’s death. There was little love lost between the Tudors and the Stuarts, whom Henry VIII specifically disinherited in his will, in the unlikely event that none of his three children produced heirs, which finally proved to be the case.

The bizarre pattern of interlocking similarities and differences begins with childhood. Elizabeth, born 7 September 1533, was a huge disappointment to her father, who had put aside one wife and broken with the church to acquire a male heir, only to receive yet another daughter. And Mary’s father, James V of Scotland, was similarly discomfited to learn of the birth of a female; having just lost his two infant sons, himself already mortally ill, upon hearing the news he turned his face to the wall in despair, and died a few days later.

But here the similarity ends. Elizabeth was shortly bastardized by her own father, who beheaded her mother on a trumped-up charge of treasonous adultery, and relegated Elizabeth to a political backwater, fraught with perils, which taught her the uses of adversity, and encouraged in her a circumspect caution which squared nicely with her Virgo Sun. Meticulous and precocious, Elizabeth spent her childhood away from the court at a series of country nursery establishments, parted also from her half-siblings for most of the time. As her father’s sometime bastard daughter, she was damaged goods in the royal marriage market, and there were rarely serious offers of matrimony.

Her road to the throne was a tortuous, twisted one, with danger lurking round every corner once her father died in 1547 and she entered her marriageable teens. Implicated tangentially in several treasonous plots against both her brother Edward VI and her sister Mary I, who succeeded their father in turn, Elizabeth was even briefly imprisoned in the infamous Tower of London, and despaired of her life. But she proved herself a survivor, succeeding her childless sister in November 1558, at the age of 25. Her road to the throne was a tortuous, twisted one, with danger lurking round every corner once her father died in 1547 and she entered her marriageable teens. Implicated tangentially in several treasonous plots against both her brother Edward VI and her sister Mary I, who succeeded their father in turn, Elizabeth was even briefly imprisoned in the infamous Tower of London, and despaired of her life. But she proved herself a survivor, succeeding her childless sister in November 1558, at the age of 25.

In stark contrast, Mary, born 8 December 1542, was never in doubt of her crown, and treated her royal status as her birthright, rather than as a dearly earned reward. Queen of Scots from within a week of her birth, Mary knew no other life. Pampered and coddled, Mary was from her infancy Europe’s prize matrimonial catch, vied for by every enterprising monarch and prince, including her great-uncle Henry VIII, who sought her as a bride for his son Edward. But Scotland’s “Auld Alliance” with the French triumphed, and she was sent at age 5 to live in France as the prospective bride of its future King, the Dauphin Francis. Raised in prominence at the extravagant Valois Court in the luxurious chateaux of the Loire valley, while Elizabeth’s governess had to beg the king her father for new underclothes, Mary’s reality was always one of wealth and unqualified, if sometimes self-interested, admiration and adoration.

Her mastery of the social graces and her obvious enjoyment of her privileged status also meshed nicely with the natural bent of her Sagittarius sun, significantly within two degrees of an exact square to her cousin Elizabeth’s. Similar in so many ways, they were also fundamentally at odds, and bound to come into conflict. Their Mercurys were in square also, Elizabeth’s at 14 Libra and Mary’s at 15 Capricorn. These two square aspects say much about the conflict which eventually eroded the outwardly cordial relations between the two queens, unique in their femaleness among the club of Europe’s sovereigns, and drawn together by ties of family and politics.

Elizabeth, often taciturn and introspective (a favorite motto was “video et taceo”—“I see all, but say nothing”), reveling in her maiden modesty and the single life, was prone to procrastination and found it difficult to make a firm decision (Libra Mercury always seeing both sides of any argument and unable to choose between them), relying on the sweep of events to determine what course she would take.

But Mary was an inveterate intriguer, passionate, willful, and quick to act without thinking through the consequences of her actions, typically Sagittarian in her outlook on life and her propensity for taking risks. Once she made a decision, she stuck to it, despite all evidence of its failure, in true Capricorn Mercury pig-headedness. She was also prone to sudden bouts of depression and near hysterical collapse, both potential trouble spots with Mercury tied to Saturn/Capricorn energies.

Elizabeth’s Mercury is quite remarkable and deserves further exploration in its own right. At 14 Libra, Mercury is the only personal planet in a Grand Cross involving Uranus/Saturn at 17/19 Cancer, Neptune at 11 Aries retrograde, and Pluto at 12 Capricorn retrograde. It is further aspected by Mars at 13 Gemini in trine.

This is an incredibly powerful Mercury, and its force in her life cannot be doubted. Elizabeth was a celebrated public speaker, highly educated even for a woman of her class, spoke four languages fluently and read Greek, and was noted for the beauty of her italic script, although her "running hand," as she called it, with which she annotated state papers, was equally noted for its illegibility. In these traits we see the predominance of Mercury/Saturn, imparting a firm intellectual basis and honing it to perfection.

She was also quick-witted, with a lively and sometimes crude, though never bawdy, sense of humor, and enjoyed putting people in some degree of psychological discomfort by her utterances or demeanor. She was quick-tempered, and could be physically abusive, as when she unintentionally broke a maid’s finger while slapping her. She enjoyed flirtation and courtship immensely, and was of a passionate nature. These reflect Mercury’s contacts to Uranus and Mars.

A master of prevarication, and a consummate actress when in public, Elizabeth’s Mercury/Neptune contact is perhaps the most vivid in her character. Her ministers were driven to distraction by her apparent inability to make a decision and stick with it. Orders were delayed, then issued, then countermanded and reissued, only to be delayed again. Elizabeth was a master of dissembling as well, and often her true intentions were cloaked in a variety of false motives, inscrutable to friends and foes alike. She became very adept at speaking or writing quite beautifully, but so circumlocutiously, as to speak without saying anything at all of substance, yet leaving the impression that she had answered every concern. She once famously replied to a delegation of Parliamentarians, sent to encourage her to dispatch her troublesome cousin, by stating: “Your judgment I condemn not, neither do I mislike your reasons, but pray you to accept my thankfulness, excuse my doubtfulness, and take in good part my answer, answerless.” Elizabeth may have been the originator of the “nondenial denial.” The Tudor Queen also had a fascination for the occult, granting special protection to the noted astrologer and mathematician Dr. John Dee, whose studio she visited occasionally.

Mercury/Pluto is harder to define, but may be seen in a more-than-usual morbid fear of death, perhaps not surprising given the execution during her impressionable youth of her mother, one step-mother, a horde of lesser relations and civil servants, and the object of her first infatuation, Thomas Seymour. It speaks also to the power Elizabeth gained, as sovereign, over the lives and deaths of her subjects.

A further circumstance which seems of utmost importance in understanding the underlying dynamic between the two queens is the placement of their respective nodal axes. Born nine years apart, the cousins shared a nodal axis, but in reverse, with Elizabeth’s North Node at 23 Leo opposing Mary’s at 24 Aquarius, and thus their South Nodes each conjoin the North Node of the other. This inverse relationship speaks volumes for the strange, mirror-like resonance in their lives, wherein sometimes their circumstances and actions mimicked one another, and sometimes stood in stark contrast, yet unmistakably linked. Opposed Nodes in conflict is a zero-sum game, and when one wins, the other inevitably loses.

Marriage, in particular, is an arena fertile with examples of their odd interconnectedness. Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen, of course never married; Mary married three times, each one a disaster in its own way.

And yet, at the outset, it was Elizabeth who had the reputation as a promiscuous flirt, and Mary that of modesty and propriety. These roles were to reverse themselves quite dramatically as time went on, Elizabeth acquiring an aura of virgin, almost semi-divine, chastity, God’s handmaiden; while Mary took on the aspects of a sexually voracious virago, depicted as a mermaid—sixteenth century metaphoric shorthand for prostitute—and greeted with cries of “Burn the whore!” from her own people after the murder of her second husband and her subsequent third marriage, to his murderer.

1560 was a significant year for both of them, and illustrates the complexities of their inverse relationship. In that year, both queens were affected by the death of someone close to them, which irrevocably changed their marriage prospects, and their destinies.

Throughout that summer, Elizabeth, still unmarried after two years on the throne, and approaching the spinsterish age of 27, was seen to be head over heels in love with Lord Robert Dudley, an acquaintance from her childhood, who was Master of the Horse and had quite swept his sovereign off her feet. Rumors of their improper familiarity spread like wildfire throughout the courts of Europe, seriously damaging Elizabeth’s reputation. There was, however, one major impediment to their love—namely, Lord Robert already had a wife.

Or at least he did until September of that year, when Amy Dudley was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in their country home, her neck broken, and no witness to her demise. Or at least he did until September of that year, when Amy Dudley was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in their country home, her neck broken, and no witness to her demise.

Murder was immediately suspected, as with any too-convenient death in the sixteenth century, and rumor pointed to Dudley, Amy’s husband and Elizabeth’s reputed lover. In Paris Mary Stuart archly quipped that “the Queen of England is about to marry her horse keeper, and he has killed his wife to make room for her.”

But Elizabeth did not marry Dudley. She sent him from court, ordered an inquiry into his wife’s death, and only after the jury found that death to be accidental was he readmitted to favor, though never again to the same prominence he had once held. Elizabeth had stood upon the brink of ruin, looked into the precipice, and wisely backed away.

That same year death ended another marriage; Mary’s 16-year-old husband, Francis II, King of France for just 18 months, died in agony in December after a brief illness, leaving Mary a childless dowager queen in a country which no longer had a place for her, but which she had come to think of as home far more than the barren, chill wasteland of Scotland. Upon their assumption of the throne in 1559, Mary and Francis had also adopted the arms and style of England, refuting Elizabeth’s right, as a bastard and heretic, to inherit that kingdom. They had not pressed their claim, and Mary’s loss meant she might no longer have the power to do so, but it also meant she would be returning to her homeland, and these two opposed queens would now be staring each other down, not from across the protective channel, but from within the same isle. That same year death ended another marriage; Mary’s 16-year-old husband, Francis II, King of France for just 18 months, died in agony in December after a brief illness, leaving Mary a childless dowager queen in a country which no longer had a place for her, but which she had come to think of as home far more than the barren, chill wasteland of Scotland. Upon their assumption of the throne in 1559, Mary and Francis had also adopted the arms and style of England, refuting Elizabeth’s right, as a bastard and heretic, to inherit that kingdom. They had not pressed their claim, and Mary’s loss meant she might no longer have the power to do so, but it also meant she would be returning to her homeland, and these two opposed queens would now be staring each other down, not from across the protective channel, but from within the same isle.

The underlying combativeness of their relationship can be seen in the synastry of their charts, particularly in Elizabeth’s Mars, which at 13 Gemini forms the apex of a Yod between them, falling inconjunct to both Mary’s 14 Scorpio Saturn and 15 Capricorn Mercury. This shows a fated circumstance arising from a conflict between power and executive authority (Mars/Saturn), based in a personal dislike, bitterness and venom (Mars/Mercury), and foreshadowing the judicial murder (Mars/Saturn) of Mary, made possible only by Elizabeth setting her signature to the death warrant (Mars/Mercury).

Additionally, Mary’s Mars at 21 Aquarius conjoins her North Node at 24 Aquarius, and is therefore also conjunct Elizabeth’s South Node at 23 Aquarius; Mary’s sexuality is very much tied up in her own destiny, for good or for ill, and only through her death can Elizabeth feel truly secure.

Mary’s chequered marital history was both the making and unmaking of her. Her betrothal and marriage to the French Dauphin elevated her from queen of a ragtag, hole-in-the-corner nation into the premiere princess of Europe; his death shattered her world and threw her back onto her own devices for the first time in her life. Her union with Henry, Lord Darnley, brought her, and ultimately Elizabeth, an heir, but was a personal disaster; Darnley was a drunken bigot who alienated everyone at court, and was a pawn for any disaffected noble who sought to legitimize his rebellion. It was his murder, in which Mary was thought to have colluded, which decisively turned the tide of history against her.

In a particularly fascinating reversal of the Amy Dudley death seven years before, it was now Mary who found herself implicated in the death of a marriage partner which held serious ramifications for the stability of her throne. Begun in an excess of passion, Mary’s relationship with Darnley had rapidly deteriorated from tenderness and bonhomie to repulsion and disgust. Jealous of anyone else’s influence over his wife, Darnley had connived in the murder of Mary’s favored personal secretary, before her very eyes, while she was heavily pregnant, the conspirators even holding a loaded pistol to her stomach. Mary’s initial shock and hysteria quickly gave way to a cold resolve. “No more tears now,” she stated as she pulled herself together. “I will think about revenge.” She first seduced her weak-willed husband away from his co-conspirators in the murder, leaving them defenseless from her retribution. Their fall left her husband defenseless in his turn. In a particularly fascinating reversal of the Amy Dudley death seven years before, it was now Mary who found herself implicated in the death of a marriage partner which held serious ramifications for the stability of her throne. Begun in an excess of passion, Mary’s relationship with Darnley had rapidly deteriorated from tenderness and bonhomie to repulsion and disgust. Jealous of anyone else’s influence over his wife, Darnley had connived in the murder of Mary’s favored personal secretary, before her very eyes, while she was heavily pregnant, the conspirators even holding a loaded pistol to her stomach. Mary’s initial shock and hysteria quickly gave way to a cold resolve. “No more tears now,” she stated as she pulled herself together. “I will think about revenge.” She first seduced her weak-willed husband away from his co-conspirators in the murder, leaving them defenseless from her retribution. Their fall left her husband defenseless in his turn.

Her false reconciliation with Darnley did not last long, and within months they were once again not on speaking terms, Mary regretting being yoked to this man and wondering aloud how she could be rid of him. She was seen to rely heavily upon a handsome nobleman, the Earl of Bothwell, and there were rumors of their affair. After another contrived reunion, whereby Mary secured Darnley’s removal from his family’s protective custody, her husband was found strangled in the garden of his exploded house outside Edinburgh.

As with Elizabeth and Dudley, suspicion of complicity fell on Mary; but unlike her English cousin, who had sent away her lover and the chief suspect, Mary actually began an affair with the man reputed to have killed her husband. Where Elizabeth had insisted upon the impartiality of a jury trial for Amy Dudley’s death, Mary seemed unconcerned with bringing to justice Darnley’s murderers. When his father pressed a claim against Bothwell, Mary allowed the case to proceed, but forbade him to enter the capital with more than a small retinue. In contrast thousands of Bothwell’s armed supporters lined the streets of Edinburgh, and Darnley’s father dropped the suit in fear of his life. Next Mary and her lover staged an abduction and rape, to clear the way for their hasty marriage, with Mary scandalizing Catholic Europe by marrying according to the Protestant rite of her new husband.

It was this third marriage, to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, the man who murdered Darnley, which brought her to lose her kingdom and her liberty, and ultimately her life. Defeated by rebellious nobles and forced to abdicate in favor of her infant son, separated from Bothwell and imprisoned in Loch Leven, Mary was reviled by her people and scorned by her European peers. A year later she escaped, raised an army, but was again defeated, and, shearing her long red hair to avoid recognition, fled south into England. It was this third marriage, to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, the man who murdered Darnley, which brought her to lose her kingdom and her liberty, and ultimately her life. Defeated by rebellious nobles and forced to abdicate in favor of her infant son, separated from Bothwell and imprisoned in Loch Leven, Mary was reviled by her people and scorned by her European peers. A year later she escaped, raised an army, but was again defeated, and, shearing her long red hair to avoid recognition, fled south into England.

So Elizabeth and Mary were destined to come into conflict, and considering the hands that fate had dealt them, there could probably be only one result in this high-stakes game, played for a kingdom. Elizabeth’s Virgoan pragmatism would trump Mary’s Sagittarian impetuosity every time, given the disparity in their resources. If Mary had remained Queen of France also she might have rolled the dice and won, but as her resources dwindled with her return to Scotland, so, too, did her options, and when her political and personal mistakes overwhelmed her position north of the border, Mary crossed that line and in 1568 threw herself on the mercy and protection of her English cousin.

But Mary’s catalog of disastrous relationships with men is not quite finished. Even after her imprisonment, her romantic and political intrigues with the Duke of Norfolk, England’s premier peer and a close maternal connection of Elizabeth’s, cost him his head.

Mary’s unexpected arrival and plea for aid presented Elizabeth with a unique and thorny problem. Although Mary herself was a Catholic, her kingdom had converted to Protestantism during her mother’s regency while Mary was away in France, and her nobles had insisted that her own son James be raised in the new faith. Mary had always intrigued for Elizabeth’s crown on the basis that, as a member of the True Religion, she was rightful heir; if Elizabeth restored her to her Scottish throne, she would doubtless continue those intrigues with foreign Catholic powers. If Elizabeth kept her in England, she would become a focus for Catholic and reactionary discontent within Elizabeth’s own kingdom.

The matter of their religions is another point of similarity and difference between the two queens. Both were heralded as exemplars of their faith, becoming icons of their respective religions, and both were subsequently demonized by the opposition. Mary’s martyrdom and Elizabeth’s deification into Gloriana are part and parcel of the same energy. Yet though they became the focus of their more zealous co-religionists, both women personally were remarkably tolerant of other points of view, Mary working effectively with her Protestant nobles when she first returned to Scotland, and Elizabeth stating she had no desire to “open windows into men’s souls;” outward conformity to the state religion would suffice. Elizabeth’s lack of sympathy for dogma and fanaticism was notorious; as she once expressed herself to the French ambassador: “There is only one Jesus Christ, one faith. All else is a dispute over trifles.”

Both women have strong contacts from the sun to spiritual planetary energies. Elizabeth’s 23 Virgo sun squares her natal Jupiter at 23 Sagittarius, and Mary’s 25 Sagittarius sun is trine her 21 Aries Neptune. These positions perfectly portray both Elizabeth’s role as Supreme Head of the Church of England and her love of liturgy and ritual which got her into trouble with her more puritanical subjects; and Mary’s intense identification with the role of martyr. Hers was a more mystical and personal connection to the divine than Elizabeth’s formal, pragmatic religion (as did most Englishmen of the time, Elizabeth had in her life conformed to every variety of official religion going, from Henrician Anglicanism to Edward VI’s militant Protestantism and Mary I’s orthodox Catholicism, until herself settling the English church into the Episcopalian form it preserves to this day).

Mary’s long imprisonment in England lasted nearly 20 years; for much of this time she represented a serious danger to Elizabeth, both from foreign intervention and domestic uprisings on her behalf. Protestant England, whose very survival hung on the slender thread of Elizabeth’s life, importuned their Queen to marry, and bayed loudly for Mary’s blood, but Elizabeth fended off both these attempts to curtail her prerogative, remaining ostentatiously single and without heirs, and refusing to sanction her cousin’s death.

Mary was tried for Darnley’s murder, and extremely damning evidence was produced in her own hand, acknowledging complicity in the deed, letters whose authenticity has been of considerable controversy to this day. Mary claimed these were forgeries, and denied the right of any court to condemn her, arguing that as an anointed sovereign she had no peers but Elizabeth, and no judge but God. Elizabeth refused either to hear Mary’s case in person, or to endorse the guilty verdict imposed by her councilors, and Mary’s captivity continued.

The Queen of Scots’ embittered intrigues bore fruit in more than one abortive attempt at invasion or assassination, and more than once Parliament took up her case with a view to forcing Elizabeth into action, but to no avail. At last, in 1586, via the use of double agents and a spy network which was the envy of the age, incontrovertible evidence of Mary’s complicity in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth and usurp the throne was discovered. Cornered, Mary denied everything, and fell back on her status as an anointed queen. As she expressed it to her jailer, Sir Amyas Paulet: “As a sinner I am truly conscious of having often offended my Creator and I beg him to forgive me, but as a Queen and Sovereign, I am aware of no fault or offence for which I have to render account to anyone here below.” Elizabeth prevaricated, delaying the inevitable execution for almost four months and then denying she had ever intended it, once the deed was done.

Mary met her end by the axe, at Fotheringay Castle on February 8, 1587, going out with a typically Sagittarian flourish. She wore a black outer garment as she ascended the scaffold, but when it was removed by her ladies, it revealed a scarlet petticoat, the color of Catholic martyrdom. When the executioner lifted the severed head, its red wig came away in his hands, leaving her skull behind; underneath the false, luxuriantly curled locks, Mary’s close-cropped hair was grey and balding. Mary met her end by the axe, at Fotheringay Castle on February 8, 1587, going out with a typically Sagittarian flourish. She wore a black outer garment as she ascended the scaffold, but when it was removed by her ladies, it revealed a scarlet petticoat, the color of Catholic martyrdom. When the executioner lifted the severed head, its red wig came away in his hands, leaving her skull behind; underneath the false, luxuriantly curled locks, Mary’s close-cropped hair was grey and balding.

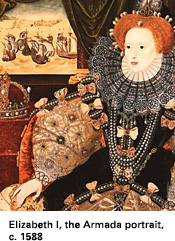

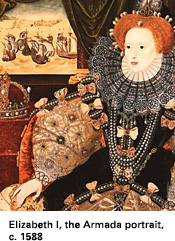

When she heard the news, Elizabeth stormed and raged for weeks, shouting down her councilors and asserting that she had signed Mary’s death warrant for reasons of safety only, and had never meant for it to be carried out. Mary’s son in Scotland, and her former brother-in-law in France, made martial noises, but did nothing. It was left to Philip II of Spain, Elizabeth’s longtime rival, to whom Mary had bequeathed her claim to the English throne, to attempt to avenge her death, which he did with his “Invincible Armada” of the following year.

There is a second synastric Yod which forms between the two charts—created by Elizabeth’s 19 Cancer Saturn inconjunct to both Mary’s 25 Sagittarius sun and her 21 Aquarius Mars. We can see here the repetition of the themes of death and justice, executive punishment and power, and frustrated ambition, which colored so much of these two queens’ lives and brought Mary to her violent death.

Ironically, it was the victory of Elizabeth’s soldiers and seamen over the Armada which cemented her reputation as a formidable stateswoman, and earned her the lasting love of her people, elevating her to the status of an icon in their eyes. Without Mary’s tragic end, and the crisis it provoked, Elizabeth’s apotheosis would have been incomplete. Ironically, it was the victory of Elizabeth’s soldiers and seamen over the Armada which cemented her reputation as a formidable stateswoman, and earned her the lasting love of her people, elevating her to the status of an icon in their eyes. Without Mary’s tragic end, and the crisis it provoked, Elizabeth’s apotheosis would have been incomplete.

But it was Mary who would prove the final victor. Sixteen years after her death, it was her son James VI of Scotland who rode south in the wake of Elizabeth’s funeral procession, joining the two kingdoms as James I, first monarch of a united Britain. And it is Mary's blood which flows in the namesake of the Virgin Queen who sits upon the English throne today.

Alex Miller-Mignone is a professional writer and astrologer, author of The Black Hole Book and The Urban Wicca, former editor of "The Galactic Calendar," and past president of The Philadelphia Astrological Society. Alex Miller-Mignone is a professional writer and astrologer, author of The Black Hole Book and The Urban Wicca, former editor of "The Galactic Calendar," and past president of The Philadelphia Astrological Society.

His pioneering work with Black Holes in astrological interpretation began in 1991, when his progressed Sun unwittingly fell into one. Alex can be reached for comment or services at Alixilamirorim@aol.com.

|

|

|

Alex Miller-Mignone is a professional writer and astrologer, author of The Black Hole Book and The Urban Wicca, former editor of "The Galactic Calendar," and past president of The Philadelphia Astrological Society.

Alex Miller-Mignone is a professional writer and astrologer, author of The Black Hole Book and The Urban Wicca, former editor of "The Galactic Calendar," and past president of The Philadelphia Astrological Society.

Her road to the throne was a tortuous, twisted one, with danger lurking round every corner once her father died in 1547 and she entered her marriageable teens. Implicated tangentially in several treasonous plots against both her brother Edward VI and her sister Mary I, who succeeded their father in turn, Elizabeth was even briefly imprisoned in the infamous Tower of London, and despaired of her life. But she proved herself a survivor, succeeding her childless sister in November 1558, at the age of 25.

Her road to the throne was a tortuous, twisted one, with danger lurking round every corner once her father died in 1547 and she entered her marriageable teens. Implicated tangentially in several treasonous plots against both her brother Edward VI and her sister Mary I, who succeeded their father in turn, Elizabeth was even briefly imprisoned in the infamous Tower of London, and despaired of her life. But she proved herself a survivor, succeeding her childless sister in November 1558, at the age of 25. Or at least he did until September of that year, when Amy Dudley was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in their country home, her neck broken, and no witness to her demise.

Or at least he did until September of that year, when Amy Dudley was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in their country home, her neck broken, and no witness to her demise. That same year death ended another marriage; Mary’s 16-year-old husband, Francis II, King of France for just 18 months, died in agony in December after a brief illness, leaving Mary a childless dowager queen in a country which no longer had a place for her, but which she had come to think of as home far more than the barren, chill wasteland of Scotland. Upon their assumption of the throne in 1559, Mary and Francis had also adopted the arms and style of England, refuting Elizabeth’s right, as a bastard and heretic, to inherit that kingdom. They had not pressed their claim, and Mary’s loss meant she might no longer have the power to do so, but it also meant she would be returning to her homeland, and these two opposed queens would now be staring each other down, not from across the protective channel, but from within the same isle.

That same year death ended another marriage; Mary’s 16-year-old husband, Francis II, King of France for just 18 months, died in agony in December after a brief illness, leaving Mary a childless dowager queen in a country which no longer had a place for her, but which she had come to think of as home far more than the barren, chill wasteland of Scotland. Upon their assumption of the throne in 1559, Mary and Francis had also adopted the arms and style of England, refuting Elizabeth’s right, as a bastard and heretic, to inherit that kingdom. They had not pressed their claim, and Mary’s loss meant she might no longer have the power to do so, but it also meant she would be returning to her homeland, and these two opposed queens would now be staring each other down, not from across the protective channel, but from within the same isle. In a particularly fascinating reversal of the Amy Dudley death seven years before, it was now Mary who found herself implicated in the death of a marriage partner which held serious ramifications for the stability of her throne. Begun in an excess of passion, Mary’s relationship with Darnley had rapidly deteriorated from tenderness and bonhomie to repulsion and disgust. Jealous of anyone else’s influence over his wife, Darnley had connived in the murder of Mary’s favored personal secretary, before her very eyes, while she was heavily pregnant, the conspirators even holding a loaded pistol to her stomach. Mary’s initial shock and hysteria quickly gave way to a cold resolve. “No more tears now,” she stated as she pulled herself together. “I will think about revenge.” She first seduced her weak-willed husband away from his co-conspirators in the murder, leaving them defenseless from her retribution. Their fall left her husband defenseless in his turn.

In a particularly fascinating reversal of the Amy Dudley death seven years before, it was now Mary who found herself implicated in the death of a marriage partner which held serious ramifications for the stability of her throne. Begun in an excess of passion, Mary’s relationship with Darnley had rapidly deteriorated from tenderness and bonhomie to repulsion and disgust. Jealous of anyone else’s influence over his wife, Darnley had connived in the murder of Mary’s favored personal secretary, before her very eyes, while she was heavily pregnant, the conspirators even holding a loaded pistol to her stomach. Mary’s initial shock and hysteria quickly gave way to a cold resolve. “No more tears now,” she stated as she pulled herself together. “I will think about revenge.” She first seduced her weak-willed husband away from his co-conspirators in the murder, leaving them defenseless from her retribution. Their fall left her husband defenseless in his turn.  It was this third marriage, to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, the man who murdered Darnley, which brought her to lose her kingdom and her liberty, and ultimately her life. Defeated by rebellious nobles and forced to abdicate in favor of her infant son, separated from Bothwell and imprisoned in Loch Leven, Mary was reviled by her people and scorned by her European peers. A year later she escaped, raised an army, but was again defeated, and, shearing her long red hair to avoid recognition, fled south into England.

It was this third marriage, to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, the man who murdered Darnley, which brought her to lose her kingdom and her liberty, and ultimately her life. Defeated by rebellious nobles and forced to abdicate in favor of her infant son, separated from Bothwell and imprisoned in Loch Leven, Mary was reviled by her people and scorned by her European peers. A year later she escaped, raised an army, but was again defeated, and, shearing her long red hair to avoid recognition, fled south into England.  Mary met her end by the axe, at Fotheringay Castle on February 8, 1587, going out with a typically Sagittarian flourish. She wore a black outer garment as she ascended the scaffold, but when it was removed by her ladies, it revealed a scarlet petticoat, the color of Catholic martyrdom. When the executioner lifted the severed head, its red wig came away in his hands, leaving her skull behind; underneath the false, luxuriantly curled locks, Mary’s close-cropped hair was grey and balding.

Mary met her end by the axe, at Fotheringay Castle on February 8, 1587, going out with a typically Sagittarian flourish. She wore a black outer garment as she ascended the scaffold, but when it was removed by her ladies, it revealed a scarlet petticoat, the color of Catholic martyrdom. When the executioner lifted the severed head, its red wig came away in his hands, leaving her skull behind; underneath the false, luxuriantly curled locks, Mary’s close-cropped hair was grey and balding. Ironically, it was the victory of Elizabeth’s soldiers and seamen over the Armada which cemented her reputation as a formidable stateswoman, and earned her the lasting love of her people, elevating her to the status of an icon in their eyes. Without Mary’s tragic end, and the crisis it provoked, Elizabeth’s apotheosis would have been incomplete.

Ironically, it was the victory of Elizabeth’s soldiers and seamen over the Armada which cemented her reputation as a formidable stateswoman, and earned her the lasting love of her people, elevating her to the status of an icon in their eyes. Without Mary’s tragic end, and the crisis it provoked, Elizabeth’s apotheosis would have been incomplete.